In times of unspeakable horrors befalling human beings, those of us who fight the undeclared war against animals, with its attendant death toll, misery, displacement and bloodshed, are often told to concentrate on “what’s important” and to give our work for animals a rest. The fact is that wars involve animals, as is recognized by the memorials to their involuntary military service, but there’s more than that.

Wars increase the everyday horrors experienced by those who happen not to have been born human, whose human guardians, if they had any, vanish, leaving them to starve, freeze and die from injuries. Then, witness the overloaded donkeys carrying panicked families fleeing Gaza. Their heads are bowed in depression, their muscles strained to the point of tearing and sometimes beyond, their legs aching from hours of pounding the pavement. Human hospitals are full and medicines depleted, so what chance for the donkeys, dogs and cats abandoned as people flee Ukraine, Azerbaijan, Palestine and other parts of the beleaguered world? Video of their plight can be seen on the PETA website and others.

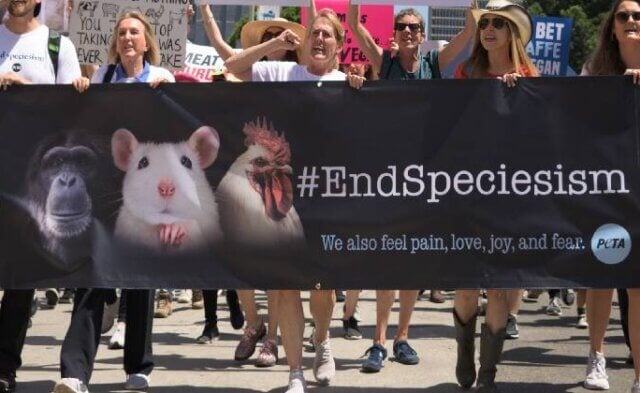

Long ago, I addressed a conference on nonviolence in Bethlehem, attended by President Jimmy Carter’s peace envoy and a host of mainly—but not exclusively—Jewish and Palestinian advocates for negotiation in the Middle East. Many speakers told tales of imprisonment, injustice, loss of family members and freedom and being treated with hatred and discrimination. Almost every speaker ended with a plea for understanding and words to the effect of “for are we not human beings?” Noting this, I ended my appeal for nonviolence to start at the breakfast table, pointing to the slaughterhouse we all passed on our way to the hall each morning, asking that we humans sweep aside our prejudice toward others who feel as much pain and fear as any human does and decide to think of ourselves as being part of a larger community. To say, “for are we not living beings?”

In 1917, two years before she was assassinated by the secret police, Rosa Luxemburg, a peace activist jailed for opposition to World War I, wrote from her cell in Breslau Prison about war and the use of animals. She recounted how soldiers outside her window mercilessly flogged a team of buffaloes who were war trophies from Romania. She wrote, “A lorry came laden with sacks, so overladen indeed that the buffaloes were unable to drag it across the threshold of the gate. The soldier-driver belabored the poor beasts so savagely with the butt end of his whip that the wardress at the gate, indignant at the sight, asked him if he had no compassion for animals. ‘No more than anyone has compassion for us men,’ he answered with an evil smile, and redoubled his blows.”

Eventually, the animals, utterly exhausted, succeeded in drawing the load over the obstacle and stood perfectly still. Luxemburg wrote, “The one that was bleeding had an expression on his face and in his soft black eyes like that of a weeping child—one who has been severely thrashed and does not know why, nor how to escape from the torment of ill-treatment.” She thinks of where these buffaloes have come from, the rich, green meadows of another land, and how they are now objects of disdain for their “nationality” and concludes, “I had a visitation of the splendor of war!”

Those of us who witness the despair of animals in war and outside it and who work to rescue animals from human oppression and aggression appeal for mercy, understanding, empathy, sympathy, fairness and an end to the prejudices that beget all violence. There may be little we can do as individuals to end wars, but we can certainly, definitely, bring peace to others through personal acts of kindness and consideration.