In linguistics, there’s a hypothesis known as “linguistic relativity,” which suggests that our native language shapes our thoughts and behavior. While scholars debate the extent to which we’re bound by the constraints of language, there is general agreement that our words influence our actions and the ways in which we experience the world.

If you looked at social media or the news in December, you may have heard about PETA’s list of idioms that aims to replace common phrases in the English language that perpetuate violence toward animals. Rather than “killing two birds with one stone,” PETA proposed, we should “feed two birds with one scone.” Instead of “bringing home the bacon,” we can show compassion toward pigs by “bringing home the bagels.”

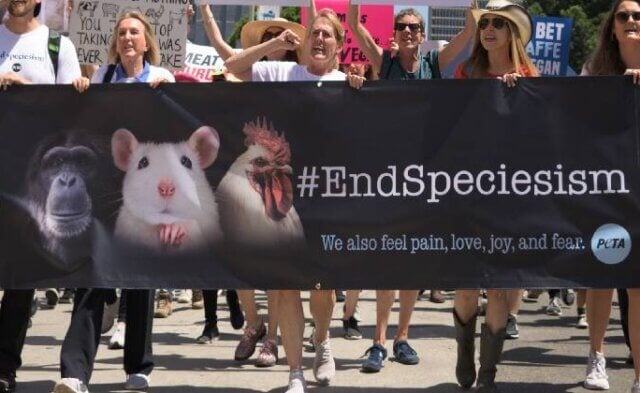

Words matter, and as our understanding of social justice evolves, our language evolves along with it. Here’s how to remove speciesism from your daily conversations. pic.twitter.com/o67EbBA7H4

— PETA (@peta) December 4, 2018

Judging by metrics alone, the campaign was a huge success. A single tweet about the phrases went viral overnight and set off a media firestorm. In just three days in December, PETA saw as many Twitter impressions as it did during the entire month of November, and PETA’s Facebook post about the idioms reached over 3 million people. The Washington Post , USA Today , CNN , and other top outlets that had probably never used the word “speciesism” before exposed countless readers to the idea at the heart of PETA’s mission—that animals are not ours to abuse.

But to what extent could changing an age-old idiom actually improve an animal’s life? Does the bull really care if you metaphorically “take him by the horns,” as opposed to “taking a flower by the thorns”?

He doesn’t understand our language any more than we understand his, so probably not. But through the lens of linguistic relativity, it’s easier to see how an apparently innocuous phrase can reinforce archaic and harmful views about our relationships with other animals. Idioms like these can send children the dangerous message that cruelty to animals is acceptable.

And in fact, many people do believe that violence toward bulls is acceptable and even entertaining. In rodeos, riders torment bulls with electric prods, spurs, and bucking straps in order to irritate and enrage them. At the “Running of the Bulls” in Pamplona, Spain, terrified bulls are forced onto city streets amid raucous crowds of tourists and handlers who hit them with sticks. They often break bones or sustain other injuries as they stumble and fall or crash into walls in their panic. Later that night, exhausted, they’re forced into the bullring, where they face a slow and gruesome death at a bullfighter’s sword.

Saying, “Take the flower by the thorns,” isn’t going to be the deciding factor in ending cruelty to bulls, but as PETA works to combat the epidemic of youth violence toward animals , we should do everything in our power to tap into children’s innate awareness of others’ rights and interests, including those of other species, and guide it toward compassion. Children learn many social norms through speech, and the adoption of more compassionate language is essential to our evolution toward a kinder society. When we examine the impact that our words have on our perceptions and, more importantly, the ways in which we treat others, we can create a better world for all beings.