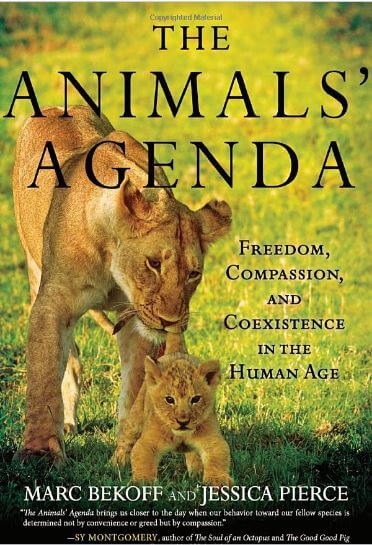

The Animals’ Agenda

By Marc Bekoff and Jessica Pierce

If Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation is considered the “Bible” of animal rights philosophy, The Animals’ Agenda is this generation’s call for pragmatic action. In sync with PETA’s laser-like focus on animal rights, ethicists Marc Bekoff and Jessica Pierce make the argument that the current animal-welfare approach, while offsetting some of the worst aspects of animal suffering, falls far short of promoting true animal well-being and freedom.

At its core, the book rightfully claims that we already know how animals suffer on factory farms and in laboratories, circuses, zoos, etc. It’s past time for us to shift from focusing on what happens to effecting a paradigm shift that will end this suffering. The entire book is filled with abolitionist-focused ideas and has chapters on experiments, food, entertainment, companion animals, and wildlife. While scholarly, it’s engaging and easy to read and understand. There are great descriptions using plain language—for example, we “are seriously and systematically constraining [animals’] freedom to mingle socially, roam about, eat, drink, sleep, pee, poop, have sex, make choices, play, relax and get away from us.” While liberally sprinkled with empirical evidence, the text flows well and the stories of individual animals are engaging and moving.

Calling it “overused,” the authors describe how the word “humane” has become so diluted that it’s meaningless. “If you hear the word ‘humane,’ you can pretty well bet that something bad is happening to animals and somebody is trying to clean it up and make it look less ugly,” they write.

The authors consider the concept of the “Five Freedoms”—which originated in the burgeoning animal-welfare movement of the U.K. in the 1960s—to have been forward thinking for its time. Essentially, it covers freedom from hunger, discomfort, pain, fear, and inappropriate living conditions. However, the authors point out that these “incredibly minimal requirements” have become the default measuring stick for “what animals want and need.” Yet for animals used in human enterprises, freedom is the most fundamental thing that they don’t have. Providing them with only the minimal requirements to stay alive is the antithesis of freedom, yet animal welfare tends to focus on just that.

Bekoff and Pierce call on readers to take a close look at the many ways in which animals are denied their freedom and then to find ways to provide them with more, not less, of what they really want and need. We need to recognize that we are part of a larger community—and that we must share the planet, not utterly dominate it. The authors’ keen intelligence, critical-thinking skills, and eloquence make this book stand out.

If non-activists read The Animals’ Agenda with an open heart and mind, it may well “reach” them. But anyone reading the book will be compelled to stop and give some thought to the impact of their choices on animals.