In most sports, medication abuse is taken seriously. Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens have been denied induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame repeatedly. Lance Armstrong was stripped of all seven of his Tour de France victories and has been banned for life from sanctioned cycling events.

But in horse racing, the abusers are elected to the Hall of Fame.

On the eve of the 2016 Kentucky Derby, Thoroughbred trainer Steve Asmussen was chosen for induction into the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame. The racing reporters and writers who voted him in essentially condoned the behavior of a trainer who, in the words of Bernard Goldberg of HBO Real Sports, has “two reputations. I think one reputation is, one of the very, very top trainers of all time. The other reputation is, here’s a guy who’ll cut corners, who’ll give his horses drugs to get ’em out on the track, because they’re not making any money unless they are out on the track.”

With this vote, racing writers scoffed at meaningful reform to spare horses from dying on the track and harmed the sport they claim to love. They should be ashamed of themselves.

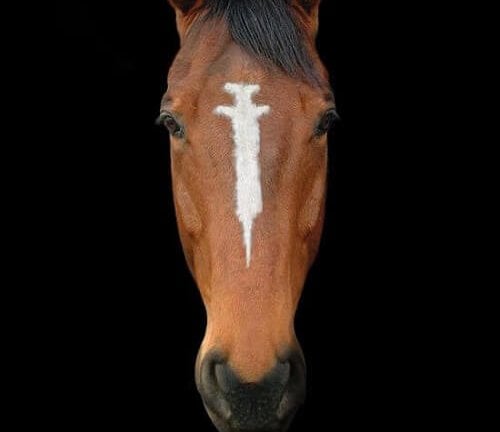

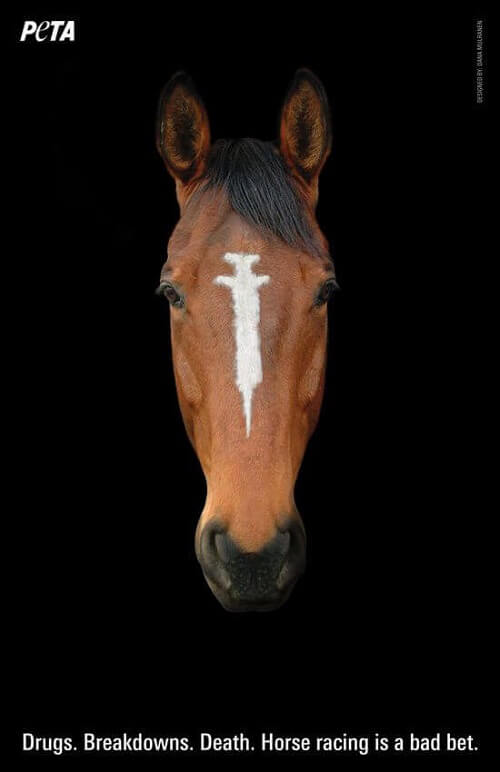

Last November, the New York State Gaming Commission released its report on evidence submitted by People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA) following our 2013 investigation of Asmussen. The Commission found that he had given horses the hormone thyroxine without medical necessity and fined him $10,000 for administering it to at least 45 horses within 48 hours of a race. More importantly, based on the evidence that PETA submitted showing the near-daily use of sedatives, painkillers and anti-inflammatory drugs, the commission introduced, in its own words, “sweeping new regulations.” According to Commission Executive Director Robert Williams, the evidence from Asmussen’s barn “prompted the Commission to put forth substantial changes to further combat the entrenched drug culture in horse racing.”

The proposed rules mandate that no drug be given to a horse except as an actual medical therapy, that all metabolism-modifying drugs be tightly controlled, that veterinarians renew prescriptions based only on their medical judgment, that the unnecessary use of any substance that abnormally affects a horse be prohibited, and that trainers keep a log of all dispensed medicines administered by the stable.

Unfortunately, this came too late for Finesse. Just days after PETA submitted its complaints to authorities, the Asmussen-trained Thoroughbred collapsed after a race and died of a “cardiac event.” Asmussen later admitted to HBO’s Goldberg that Finesse had been given thyroxine as well as clenbuterol and Lasix.

Asmussen is certainly not the only trainer with a history of drug violations. Yet when PETA released a video of the Asmussen investigation in 2014, many in racing wrote movingly of the need to reform medication rules for the benefit of the horses and the survival of racing. The link between overmedication and breakdowns on the track was acknowledged. Many vowed to fight for reform. The Jockey Club promised to introduce medication reform legislation and indeed, in 2015, worked with members of Congress to do so.

Yet for many in racing, including the columnists and writers whose job it is to cover the facts, it’s back to the same old deadly business as usual.

Asmussen is training one of the Derby favorites this year, Gun Runner, and his win and earnings totals cannot be disputed, but how did he earn this? Being recognized as one of the elite of racing should entail much more than simply racking up a high volume of wins. Achieving meaningful change in horse racing would be easier if the men and women who write about it acknowledged that the overuse of medication leads to breakdown and death and must be stopped.