At one time or another, many of us in the animal rights movement have attempted to lobby politicians. A few of us have been able to open a few eyes and be heard. Sometimes, the attempt saddens or angers us and we leave the encounter cynical or discouraged from ever trying again. Like diving into a pool, it works out better if you can float or swim.

Lobbying is an amalgam of role-playing, persuasion, diplomacy, and understanding the battle terrain. You need to listen as much as you talk.

What it is not about is how you feel, no matter how deep your anguish and fury. It’s mostly about those officials whom you need to persuade to support laws that protect the well-being of animals.

So before we even step into the state house or town hall, we need to be versed in the dynamics that led to the election of the particular person we intend to lobby. In many cases, there’s an internet record of legislators’ votes as well as how well each one fared in the most recent election. If they received 60 percent of the vote, they’re invested in maintaining their standing in the community and you may have a difficult time getting them to address a less popular concern. If their winning margin was under 5 percent, they may be happy to garner the support of any constituent—provided that it doesn’t cost them the support of other voters.

While most legislators (like the general public) will swear that their dog, horse, or cat is a much-loved member of their family, they may regard cattle, pigs, lambs, and fowl as food, clothing, living test tubes, or sources of entertainment.

But you shouldn’t assume that the person you’re attempting to persuade to take a course of action is an unethical captive of the dark powers.

Most well-intentioned people who run for office do so because they honestly believe in a number of issues that are important to them and that they feel must be addressed and resolved. Yet once installed in office, those elected representatives aren’t free agents: They must also heed the leaders of their party and the chairs who lead jurisdictional committees through which all proposed legislation flows—or sinks.

I’ve known and worked with a number of politicians over the decades. For the purpose of my argument, I assume that politicians enter office with fixed positions on about 25 percent of the issues that the legislative body will eventually consider. They’ll likely discover that most of the other legislators with whom they must serve also have projects and laws about which they feel strongly. To get fellow legislators to support projects, they trade support and cosponsorships. Without a community of support, the legislative leadership is usually correct in assuming that a particular bill is headed for an embarrassing defeat.

Then there are those issues that the executive administration or legislative leadership has campaigned on and intends to make a hallmark of the good stewardship by its party. Accepting my guesstimates, that leaves the final 25 percent of the session’s issues without strong advocates, and these are thus left to the discretion of individual legislators and the wishes of their constituents. There’s another political axiom: The person who owns the largest megaphone is likely to carry the day. If you have donated to your rep’s campaign, have a large family of like- minded registered voters who vote as you do, or belong to community organizations in which you may have an influence on other voters, you own a powerful megaphone. If you lack all three, you still have a vote, and no politician with an ounce of common sense alienates any voter if it can be avoided.

Knowing all this before you enter your target legislator’s office will help you determine where he or she stands, not solely as a matter of conscience but also as a matter of obligation. A confirmed meat-eater who hunts for fun may not be easily persuaded to vote for animal-friendly legislation. The legislator who’s gunning for a leadership position is going to toe the party line. A maverick who has a reputation of supporting what the majority of legislators (and constituents) see as unpopular causes and fails to support his colleagues’ pet projects may be persuadable but may also be the kiss of death to your hopes. Mavericks fly solo not only by choice but also because others avoid them.

Understanding all that, it now comes down to you. In decades of trying to persuade city and state politicians to support animal issues, I watched pro-animal legislation die before it even got to a committee because of a certain strain of citizen supporters who took it upon themselves to lobby. Accusatory slogans that are useful in marches may not be appropriate or helpful when talking to your legislator. Getting angry, trying to shame your legislator, raising your voice, and making a scene or empty threats are worse than staying at home and doing nothing. Always remember: You’re talking to politicians to persuade them to take action, not to offend and forever alienate them.

PETA fights back against meat & dairy industry lobbying with a special delivery to Congress. http://t.co/N7WsP3ZH4W pic.twitter.com/xCkRnegib4

— PETA (@peta) September 18, 2015

I’ve sat down with politicians who let me know from the get-go that they were still nursing grievances against animal advocates who’d been intemperate and threatening. I spent more time mollifying them and casting the offenders as outliers than actually promoting the merits of the bill that I supported or outlining the concerns about one that I wished defeated. (Here’s a tip: Never threaten anything like “certain defeat in a bid for reelection.” Not only will you anger the person, he or she will also lose all respect for you and regard you as a blowhard joke.)

Far less important—yet still a consideration—is how you present yourself. Don’t pretend to be what you aren’t or promise what you can’t deliver. You don’t need to wear your Sunday best. Direct-from-work garb or clean casual style testifies to our roles as everyday voters—neither phonies nor nutjobs. Few politicians survive for long without being able to sense fakes.

Keep your message calmly resolute and on point with facts and logic. Thank the person for listening to you. Leave a card with your contact information and a reference note to the bill you’re campaigning for or against. Above all, don’t waste a politician’s time.

Good luck.

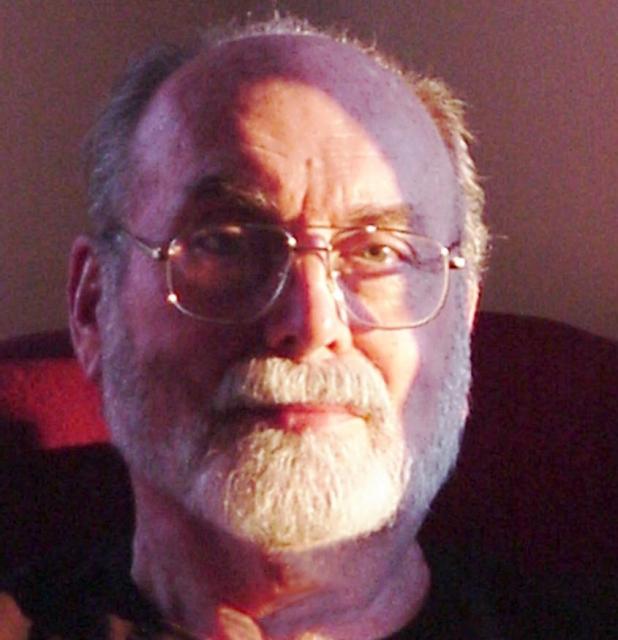

Frank Cullen spent six years as a Cambridge, Massachusetts, elected (and reelected) official and served on various commissions and boards at the city and state levels.