Every year in Yulin, China, thousands of dogs—and even a few cats—are barbarically slaughtered for a summer solstice gathering, and their flesh is sold as food.

Commonly called the Yulin dog-eating festival, this event is vehemently condemned by the international community—and by many Chinese people, too.

It’s easy to see why: The thought of killing, dismembering, cooking, and eating our animal companions is enough to make most of us lose our lunch.

But there’s no rational reason why the thought of eating any other animal shouldn’t elicit the same revulsion—especially when animals raised and slaughtered in the United States often face horrors akin to those endured by the dogs in Yulin.

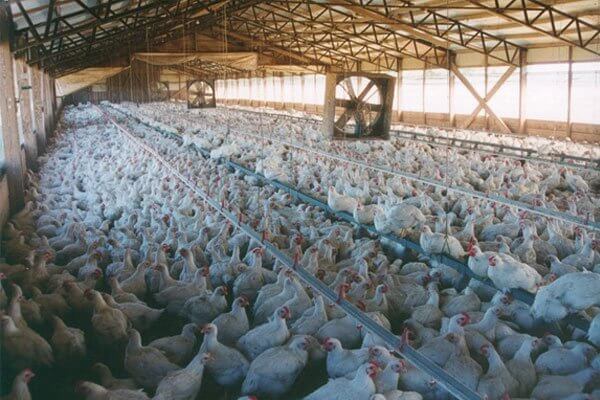

Dogs killed and eaten in Yulin are regularly transported there from other cities. They’re crammed into small cages and put on trucks, which may then travel for hundreds of miles. Along the way, they’re often deprived of food, water, and rest. The same is true for millions of chickens, pigs, cows, and other animals in the U.S. Some freeze to the sides of the transport trucks or die from dehydration. Still others are inadvertently trampled by other animals who are packed on the severely crowded trucks without enough space to lie down during the long journeys.

We’re particularly offended by the gruesome methods that are typically used to slaughter dogs in Yulin. Some are boiled alive—a horrifying death that makes most of us shudder. But right here in the U.S., countless chickens and turkeys meet a similar fate every single day: At the slaughterhouse, many of these intelligent birds manage to keep their heads from being dunked into the electrified water baths meant to stun them—leaving them conscious as their throats are slit—and many are still alive as they’re immersed in scalding-hot water to remove their feathers.

Some dogs in Yulin are clubbed on the head. This is certainly grotesque, but it’s also business as usual for commercial fishers who repeatedly bash in fish’s heads or beat live, intelligent octopuses against rocks in order to “tenderize” their flesh. Many sea animals—all with the same capacity to feel pain as any dog or cat—experience explosive decompression, and their eyes may even burst, when they’re hauled up from the depths of the sea.

Most Yulin restaurateurs believe that adrenaline adds flavor to animal flesh, which means that dogs are typically killed in full view of other dogs. This is horrifying, but imagine that you’re a pig raised in the U.S.—an animal whose cognitive abilities in many ways exceed those of dogs. You’re forced out of a truck by humans with prods. You move with your herd into a slaughterhouse that reeks of blood, and you can hear the frantic squeals of the other pigs ahead of you.

As you file into a room, your adrenaline is pumping—you see other pigs strung upside down and watch, in terror, as their throats are slit. You know you’re about to die, and there’s no escape—just like for the dogs in Yulin.

Whether a fish or a dog, a pig or a chicken, no animal wants to suffer and die for our palates.

Pointing a finger at other cultures is easy—what’s harder is facing the faults in our own behavior and correcting them.

Yes, let’s be outraged by the cruelty that occurs during the Yulin dog-eating festival, but let’s not be hypocritical about it. We should extend our compassion to all animals—not just dogs—by leaving them off our plates.

Written by Emma Hurst, media officer for PETA Australia.