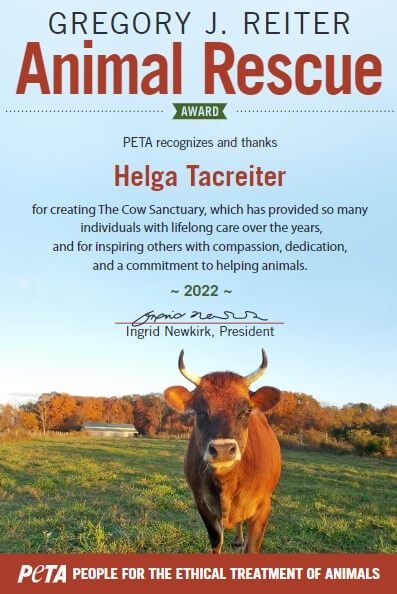

Each year, PETA memorializes the legacy of a beloved champion for animals by presenting the Gregory J. Reiter Animal Rescue Award to a group or an individual devoted to making the world a kinder place for animals. Greg’s widow, Alysoun Mahoney, continues to honor her late husband with her own commitment to animal rights and her efforts to provide rescued dogs, cats, horses, and wildlife with loving homes.

This year’s award recipient is Helga Tacreiter, founder of The Cow Sanctuary in New Jersey, who has spent her life rescuing “big, beautiful, breathing cows.”

Helga’s inspiring dedication to animals proves that she is the embodiment of Greg’s legacy. Be sure to read her interview with PETA Prime below—we bet that you, too, will be inspired to spread kindness for cows and all other animals.

Congratulations on being named the recipient of this year’s Gregory J. Reiter Animal Rescue Award! Can you describe what winning this award means to you?

Winning this award is a very wonderful pat on the back. Much of what I do on a daily basis is mundane—scrubbing and filling water tubs, hauling bags of grain, loading and unloading bales of hay, scooping poop. None of this is glorious work. What makes it matter is that the doing of it makes the lives of the animals in my care comfortable and happy. They like fresh water, clean beds, and meals served on a regular basis. I really appreciate that my 35 years of small, daily efforts are being acknowledged so publicly. In addition, the award money will be a big help—paying for a permanent underground water line to be installed for a pasture that until now depended on hoses.

What inspired you to start The Cow Sanctuary?

Shortly after graduation, I took what I thought would be a short summer job on a dairy farm. At the time, I had no idea what a dairy farm was really like. I’d only ever seen cows in a field as I drove past in a car. I thought that cows made milk the way that trees make leaves or fruit. I thought it was just what their bodies did naturally. Little did I know.

My first day on the job—my first hour, actually—I felt an immediate kinship with the cows. The best way that I can describe it is that it felt the way I had heard twins separated at birth feel when they are reunited. It was deep, almost overwhelming. Then, little by little, day by day, I learned the reality of their lives. Part of my job was separating the mother cows from their newborn calves. Another part was loading the boy calves onto a truck that took them away. Yet another part was loading the cows [who] weren’t making much milk anymore onto other trucks. At first, I had no idea where those trucks went. I asked and was told, “Cowtown.” “What’s Cowtown?” I asked. It was the auction. I went to the auction, once. I wanted to see for myself what it was. It was the place where slaughterhouses bid against each other for the cows and calves I’d put onto the trucks earlier. It was worse than I’d imagined.

This was 1976, close to 50 years ago. The farm where I worked was a family farm, with 100 cows and only two employees, me being one of them, and the farmer was a kind, decent man. There were no cattle prods, no hormones to boost production, no hitting, no overt cruelty. It was the system that was cruel, not the farmer. If the cow didn’t get pregnant each year, her body wouldn’t make milk to feed her calf. If the cow were to keep her baby, the baby would drink the milk and there’d be no milk for the farmer to sell to feed his family. I worked there for eight years, for the love of the cows. Being with them every day was heavenly. After my auction experience, I wasn’t asked to load the cows onto the trucks anymore. As I said, the farmer was a kind man. I stayed because I couldn’t see a way to change it. And I loved being with the cows.

When he turned 65, the farmer retired. He offered for me to take over the farm. I couldn’t. It was one thing to “compartmentalize,” to understand how the dairy system worked, and to work within it, but I just couldn’t be the one responsible for taking the calves from their mothers, nor for sending them—and later their mothers—to their deaths.

So I went to work on a horse farm, where I thought all would be kindness. Once again, little did I know. (But that’s another story.) Unbeknownst to me, the horse farm had a herd of black Angus “beef cattle.” One night, there was a terrible lightning storm. All the cows were killed by the lightning, except for six tiny calves. I discovered these little survivors trying to nurse on their dead mothers. I swore to myself that I’d protect them for the rest of their lives. Perhaps it would in some small way balance out the ones I’d loaded onto trucks. So, The Cow Sanctuary began, and I have rescued a total of 150 animals over the years—I’m caring for 66 right now!

When did you first get involved with PETA?

In 1988, the year that the calves were born, a friend sent me a newspaper clipping about Ingrid Newkirk and how she started PETA. I drove to PETA’s headquarters, which was at a warehouse in Washington, D.C., at the time, with the hope of meeting her. I wanted to see if she was as wonderful in person as she sounded in the article and if the other PETA people in the offices were equally dedicated. If they were as they seemed in the article, I wanted to ask if they might be able to help me place some of the calves. Although I ended up keeping all the calves myself, that visit gave me a deep respect for Ingrid and PETA. Later, they placed several cows with me.

Do you have any advice for someone who may want to start their own animal sanctuary?

Examine your motives. Are you willing to make a lifetime commitment? If nobody helps, will you still do it? Are you a practical person? (Dreamers can be practical, too.) Sanctuaries are basically farms but without the killing. Do you have the heart of a farmer? How do you feel about doing manual labor? How will you fund it? Remember, the work is for the animals’ whole lives, not just when they’re cute little babies. Can you handle old age and decline? Do you have a board or other designated people who will ensure care of the animals if you suddenly pass?

If you decide to go for it, the more room, the better! Buy and fence in as much acreage as possible. This is good advice I heard from another sanctuary: Volunteer regularly for a year at a local sanctuary so that you can learn the nuts and bolts of it. One day in beautiful spring weather, cuddling babies, is only part of it. Old folks dying in the middle of winter is part of it, too. No matter the weather or circumstance, the animals need you!

Click here to learn more about The Cow Sanctuary, Helga’s lifesaving work, and some of her favorite animal rescue stories—like that of interspecies best friends Patrick and Jerry!