Sometimes, the most lasting lesson isn’t anywhere on the syllabus.

Students in college agricultural programs are often required to raise animals and then ship them off to the slaughterhouse, and that’s exactly what undergrads in an East Coast university’s swine-production class were expected to do to the pigs they had tended to for two years.

Their instructor had advised them not to get “attached” to the eight pregnant sows, who had been kept on campus in gestation crates so small that they couldn’t even turn around. Students were told to keep in mind that these pigs are not individuals with feelings but food on the hoof and to name them according to their eventual fate. So they were tagged with callous names like “Baconator,” “BLTina,” and “Sloppy Joanne.”

On pig factory farms, after giving birth, sows are moved from gestation crates to “farrowing” crates, which are wide enough for them to lie down and nurse in but not big enough for them to turn around or build a nest for their babies in, which pigs do in nature by collecting sticks and grass. The piglets are taken away from their doting mothers when they’re as young as 10 days old so that farmers can artificially inseminate the sows again, perpetuating the cycle of exploitation and abuse that lasts for three or four years, at which point the mother pigs are sent to slaughter.

But after watching a sow give birth and lovingly nuzzle her piglets as best she could in the cramped space, one student realized that he didn’t want to be part of her death sentence or let any of the pigs be killed for the fleeting taste of their flesh. Moved and impressed by the admirable attributes that stand out to anyone lucky enough to get to know pigs—their intelligence, friendliness, and loyalty—he made the compassionate decision to buck the system and rewrite the lesson plan.

The student contacted longtime PETA friend Helga Tacreiter—who runs The Cow Sanctuary in New Jersey, a peaceful, beautiful haven for farmed animals.

“I met pigs for the first time, and they’re wonderful, intelligent creatures, and they’ve had a life of total misery,” he told her. “And I’d like to save them.”

Helga, who has taken in many animals rescued by PETA over the decades, knew that she must help. Even though money was tight, she agreed to take the pigs if the student could get legal custody of them. He dug into his own pocket, offering what he could, and when Helga contacted PETA for assistance, a guardian “angel” came to the rescue: The late Sam Simon offered to donate the asking price for the pigs, which was roughly $8,000.

But the pigs weren’t out of the woods yet. The school didn’t like the plan and hatched one of its own. Days before they were set to go to auction, the pigs went missing. The school had secretly sold them early, and they were already on a truck bound for the slaughterhouse. When the student found out, he immediately called Helga. Working together, they managed to track down the truck driver, intercept him on the road, and persuade him to change his route—for a fee.

It was nighttime when the truck pulled into the sanctuary driveway. Using flashlights, Helga, the student, one of his friends, and the truck driver gently unloaded the pigs. Exhausted, the animals curled up together in the open field and slept for nearly 24 hours straight.

One of the sows, renamed Trixie, was too ill to be saved and, despite Helga’s best efforts, died a few days after arriving at the sanctuary. But she died peacefully surrounded by people who cared about her rather than in a noisy, smelly, terrifying slaughterhouse. Helga removed the factory-farm tag from Trixie’s ear and laid her to rest in a grave on the sanctuary grounds.

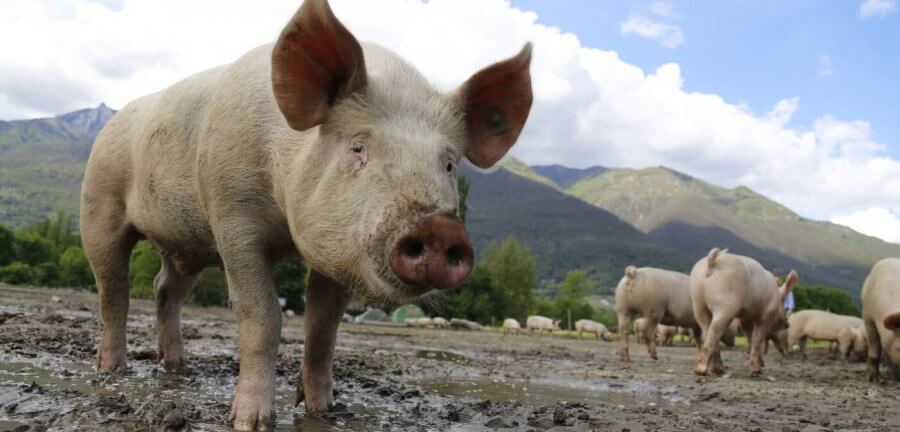

The surviving seven sows are thriving today. They love exploring the spacious grounds, rooting in the straw and earth, and doing all the other things that pigs enjoy when they aren’t condemned to suffering for their flesh. They spend hours lying in the sun, and when it gets too hot, they cool off in the mud.

Before arriving at their new home, they had never seen fresh fruit or vegetables, so they weren’t sure what to do with them. But before long, their snouts were covered with watermelon juice and their lips were stained red by strawberries.

They also run to greet Helga every time she goes out to the field. Pigs are affectionate that way, just like dogs. And just like dogs—and all other animals, including humans—pigs value their lives and experience fear, pain, love, and joy. Thanks to one student with a big heart, seven pigs are now living happily ever after. Imagine what would happen if other students learned to be just as compassionate.

That’s PETA ’s lesson plan.