For his first five weeks of life, Britches knew nothing but isolation and darkness. If he had been allowed to grow up in his natural habitat —the lush rainforests of Southeast Asia—the stump-tailed macaque would have spent his first nine months enjoying the warmth of the sun, playing with other monkeys, being groomed and protected by his nurturing mother and the other female members of the group, and foraging for tasty fruit, seeds, flowers, leaves, and other foods. He would have traveled with his troop, rested in the shade on warm afternoons, and slept high up in the trees at night.

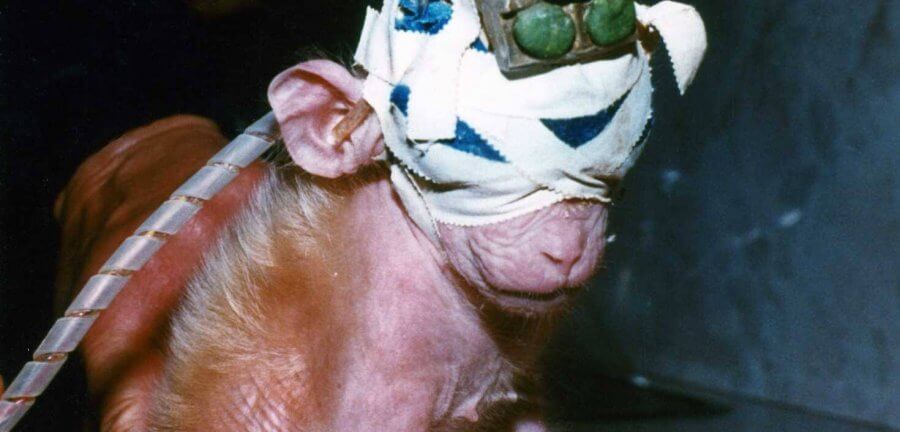

Instead, he was confined to a laboratory at the University of California–Riverside. Lazy experimenters, who were studying blindness and admitted that they couldn’t be bothered to drive out to visit blind children in their homes, tore the infant away from his mother on the very night that he was born. They crudely sewed his eyes shut with thick thread and strapped a bulky, heavy electronic sonar device that made a constant screeching sound to his tiny head—all of which was extremely distressing to him. Then, they locked him inside a barren wire cage, all alone, as part of their useless experiment.

Desperately lonely, Britches was given a wire device wrapped in cloth and equipped that served as his surrogate “mother,” and all he could do was cling to it and “nurse” from the bottle that it contained. Each new day was as dark and hopeless as the last— until the night that a team of rescuers silently entered the laboratory where he was being held, opened his cage door, and took him away from that terrible place forever. The team saved 700 other animals that night, including cats with one eye sewn shut, rabbits and pigeons who had been starved, opossums whose eyes had been mutilated before they were old enough to leave their mothers’ pouches, and mice who had been forced to eat meat or starve in nutrition experiments whose results were irrelevant to humans.

One of the daring rescuers rushed Britches to the home of a sympathetic veterinarian, who gently peeled away the massive bandage that held the sonar device to the little monkey’s head. Underneath the tape, which had been heavily layered and tightly wrapped around his face and skull, there were open sores.

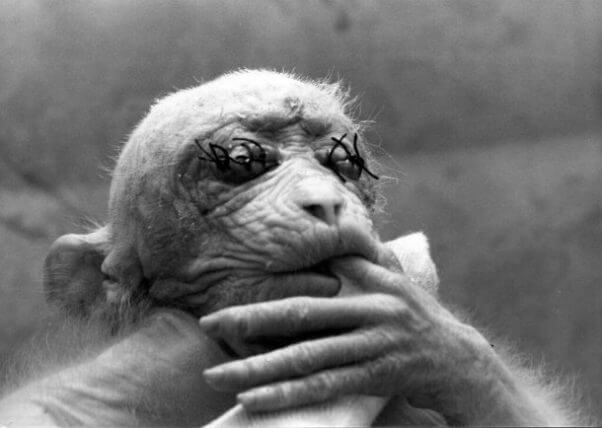

The veterinarian gasped upon seeing the thick black sutures that held Britches’ eyelids tightly shut. The stitches were so crudely sewn that many had torn right through his delicate eyelids, leaving them permanently deformed, and were rubbing against his corneas.

Ever so carefully, the veterinarian cut away the sutures and wiped away the crust that had formed around the wounds. At first, Britches didn’t realize that he could finally open his eyes. But then, slowly, he raised one eyelid and then the other. He squinted into the light, taking in the world he had never seen. Fascinated, he opened both eyes fully and turned his head from left to right, as if to say, “Wow! I can see!”

From that moment on, Britches’ world only got brighter. After months of dedicated attention from the veterinarian (who became his foster caretaker), the tiny monkey who had once shrieked in fear at the slightest sound was now playing with toys, joyfully leaping around, and gently stroking his caretaker’s face to show his affection for her.

By the time Britches was 5 months old, he was well enough to be transferred to a sanctuary with a large outdoor area to explore and other monkeys to romp and wrestle with. A female monkey there adopted him and cared for him as her own. The two quickly bonded, and Britches loved giving and receiving hugs and caresses. His mischievous side emerged, too, and sometimes he played tricks on her. But most of all, he loved looking out at his bright new world through inquisitive eyes that experimenters would have kept shut forever.

PETA publicized photographs, videotapes, and documents obtained by the rescuers, and a year after the raid at the university, documents filed by the university revealed that eight out of the 17 experiments from which animals were rescued were never resumed. The school also stopped permitting baby monkeys’ eyes to be sewn shut, and one instructor stopped experimenting on animals altogether.

Since then, PETA has helped end other cruel experiments on baby monkeys, including maternal-deprivation experiments at the National Institutes of Health, in which infant monkeys were torn away from their mothers at birth, terrorized with loud sounds and fake snakes, intimidated by experimenters, addicted to alcohol, and isolated in tiny cages in order to worsen their psychological distress. Stephen Suomi, who led this horrendous project for 30 years, is no longer involved in any experiments on animals, and his animal laboratory has been shut down.

All babies deserve to be nurtured and cared for by their mothers, but animals in laboratories are often denied this fundamental right. PETA won’t give up until no more baby animals are torn from their mothers, terrorized, and treated as living laboratory equipment.

You can help monkeys like Britches—along with dogs, cats, rabbits, and other animals condemned to suffer in cruel experiments—by donating now to stop cruel animal testing.