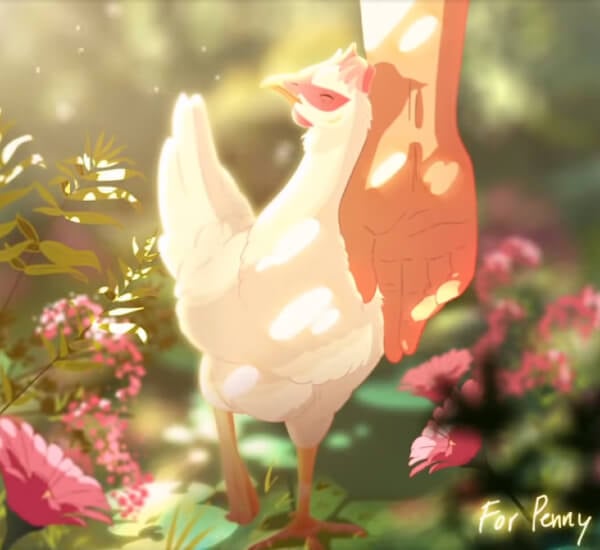

Penny was my best friend. Like many animal companions, she followed me everywhere I went, slept in the bedroom with me at night, and made sure I woke up on time for breakfast every morning. We’d spend our days having outdoor adventures and our nights lounging together on the couch.

Penny was a chicken hatched in the egg industry, and she spent the first two years of her life imprisoned in a wire cage on a typical egg farm. She was one of 18 hens my team and I found trapped among deceased hens in piles of manure that had built up as high as 5 feet underneath the cages on three egg farms in Abbotsford, British Columbia, in 2018. The footage that we captured was released as a PETA exposé, narrated by Kat Graham, to raise awareness of the horrors that chickens and other animals endure on factory farms and in slaughterhouses.

If I’d never been inside an egg farm before, I’d have been shocked at the state Penny and the other girls were left in. Prior to Penny’s rescue, I worked as an undercover investigator on many egg farms. The neglect and indifference to the suffering of birds I saw on these farms was consistent with everything I’d seen on other egg farms.

I was surprised that Penny and the other chickens were so calm when we gave them their first bath. It must have been a relief to get clean at last. With the caked-on manure removed from their bodies, they could finally preen their own feathers.

When I saw the hens engaging in natural behavior for the first time, I felt many things. It was almost magical to see them perfectly expressing natural instincts, without ever having been taught or even having seen another chicken exhibit them before. I empathized with the relief that they must have felt after years in which their natural desires were constantly frustrated. I was able to share in their joy from feeling the warmth of the sun, breathing fresh air, and exploring a new, expansive, lush green world.

All 18 chickens came to live with me that night, although not all survived the trauma that they had been forced to endure. Penny, Miley, Wilma, Josephene, and Lou Lou were among those who lived with me for just under three years. After that, to keep them safe from nearby wildlife, Penny and the remaining girls went to a farm sanctuary on Vancouver Island called A Home for Hooves.

Penny was exceptionally quiet, shy, insecure, and sweet. During their years with me, all the other hens slept in the chicken house. Penny slept in my bedroom—first lying on the bed with me and then, once she’d developed sufficient feathers and strength to fly, roosting on top of the dresser overnight. Every morning, as soon as it was light, Penny would launch onto my bed and wouldn’t get off me until I let her outside. She’d spend the day with the other hens doing chicken things. Then every evening, as soon as it started to get dark, the others would go into the chicken house and Penny would come and tap on my window to let me know she was ready to come indoors. She’d sit with me—at my feet or on the back of the couch—until she was ready to roost.

After the girls went to the sanctuary, I stayed up to date on Penny’s health issues. Unfortunately, she had many, because chickens have been genetically altered to lay a shockingly unnatural number of eggs. Wild hens lay about 10 to 15 eggs per year, but hens in the egg industry have been selectively bred to produce between 300 and 400 eggs per year. In October 2020, Penny had surgery to remove a buildup of eggs that had accumulated in her abdominal wall. Most but not all of the eggs were removed. She lived another seven months after the surgery. When she died, the veterinarians who treated her said that they believed she had an infection related to the leftover egg mass that couldn’t be removed. She was approximately 5 or 6 years old.

Penny’s life mattered simply because she could experience misery and joy. Her life mattered no less than that of any other hen hidden behind the walls of a factory farm. The difference between Penny and the billions of hens we’ll never meet is simply that we knew her. We saw her capacity to feel not only fear, pain, and misery but also excitement, curiosity, joy, and trust. We saw her desire to express natural behavior like dust-bathing, preening, roosting, and scratching in the dirt. We saw her long for companionship, safety, and comfort—and we watched her form emotional bonds with species other than her own.

Despite having worked on many egg farms before meeting Penny, I see other chickens in a new way because I knew her. They all share the same desire to be safe and free from pain, form relationships, be part of a community, and have autonomy over their own lives. They all have distinct character traits and preferences that make them individuals. When looking into the eyes of chickens, you know that there is someone there with a unique and complete experience of the world.

Thank you to everyone who no longer consumes eggs or other animal-derived products. By going vegan, we can spare countless others like Penny the horrors of factory farms and slaughterhouses.

I’m so grateful that Penny was able to spend the majority of her 6 years exploring the outdoors, foraging in the grass, dust-bathing, and stretching her wings in the sun—happy, content, and free.

*****

Geoff Regier is a Vancouver-based animal rights activist and longtime PETA supporter who spent three years as an undercover investigator working on farms and in slaughterhouses across Canada. He also takes his activism to the streets by using chalk to write messages on sidewalks and through a project called TV Outreach for Animals, in which he screens footage to passersby to inform them of the suffering that animals endure for food.