By Craig Shapiro

I went hunting once—on a friend’s farm in southwest Georgia. Some 50 years after I fired into a squirrel’s nest, I recall the shock of seeing them plummet lifelessly to the ground as vividly as if it were only a moment ago. I’m thinking about it now.

In Maine this year, a high school student gutted a doe she had killed and dragged out of the woods while her friends were celebrating Halloween. She was the last animal the girl needed to get a “grand slam” patch for “harvesting” a deer, a turkey, a bear and a moose in the same year.

The bear wasn’t her first. She’s shot five—the most recent was seeking refuge in a tree after the terrified animal had been chased for miles by a pack of hounds. Her victim’s skin is being made into a rug. It took her three shots to kill an 860-pound bull moose. After gutting him, she ate a piece of his heart and smeared his blood on her face to “connect with nature.” She saved his shoulder blades, legs and jawbone.

Across Ohio during the state’s two-day youth hunting season more than 10,000 white-tailed deer— 10,000—were killed, well above the three-year average of 7,600 between 2020 and 2022. If you believe the euphemisms, those deer were also “harvested.”

“It’s fun to know that you’re the one who killed it and you’re the one who found it and you’re going to skin and dress it and all that kind of stuff,” said one 14-year-old.

At a hearing in New York state about extending hunting season for 12- and 13-year-olds—in Missouri, 6-year-olds can be licensed to hunt—a state legislator cut to the chase, saying that hunting is an “economic driver” fueled by new generations of hunters and then reciting the specious argument that it’s important to “deer management.” It isn’t. When deer are killed, the subsequent spike in the food supply increases breeding among the survivors and attracts more deer. If “management” means reducing populations, hunting defeats the purpose.

In Wisconsin, a newspaper columnist bemoaning the dwindling number of applicants for gun deer licenses was worried that children wouldn’t learn about patience, discipline, dignity, self-reliance and generosity if they didn’t kill deer. Hunting isn’t really about guns or even antlers on a wall, he fantasized, it’s about teaching kids self-worth.

He was also worried that kids who hunt are told that it’s “cruel and unnecessary.”

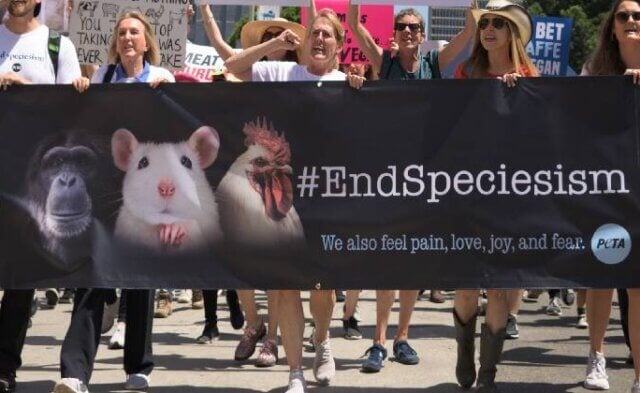

That’s because it is. Hunting’s a blood sport, and it doesn’t teach children or anyone else anything about self-worth. What it does teach them is that the lives of other beings—who, like them, experience fear and feel pain—are worthless.

Shy and inquisitive, deer only want to be left in peace to raise their families. Fawns stay at their mother’s side for as long as two years. Turkeys are affectionate, highly intelligent individuals. They enjoy exploring and form strong social bonds. Gentle and tolerant, bears can also be empathetic, playful and even altruistic. Mother bears are devoted to their cubs. Moose, who can live up to 25 years, are peaceful and rarely become aggressive. For many Native Americans, they represent wisdom, bravery and grace.

Eating a moose’s heart doesn’t connect someone to nature. We connect by recognizing that animals are the same as us in all the ways that matter. We connect by respecting their individuality and their right to live in peace.

Let’s teach our children to do that. They—and the animals—deserve it.