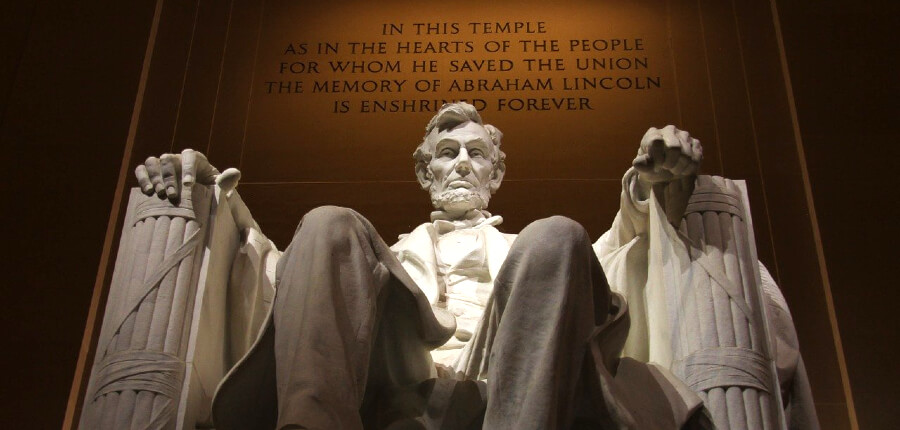

President Abraham Lincoln is one of the most honorable men ever to have served in office. Of course, he’s known for the Emancipation Proclamation and many other lasting decisions, but many may not know of his animal rights leanings—even back in the 1800s.

Young Lincoln’s affinity for animals was likely sparked by a pig who became his constant companion. The boy was just 6 years old when his family acquired a piglet, and the two quickly became best friends. They played together, roamed the woods, enjoyed games of hide-and-seek, and simply delighted in each other’s company.

As he recounted in his own words in Ferdinand C. Iglehart’s anthology The Speaking Oak, Lincoln’s “heart got as heavy as lead” when he overheard his father say he planned to kill the now full-size hog. The young boy slipped out and took the pig to the forest in a desperate attempt to hide him. But he said that he knew “all hope was gone” when he discovered that his angry father had found the pig, returned him to the pen, and slaughtered him.

“I saw the hog, dressed, hanging from a pole … and I began to blubber. I could not stand it, and went back into the woods again, where I found some nuts that stayed my appetite till night, when I returned home. They never could get me to take a bit of the meat … it made me sad and sick to even look at it.”

Fast-forward many years. In 1861, King Mongkut of Thailand (then called “Siam”) thought he was being generous when he offered President Abraham Lincoln a pair of elephants who would lead a life of servitude thousands of miles away from their natural homeland.

Ever the diplomat, Lincoln politely declined the king’s offer, stating that the U.S. used steam engines and would have no use for enslaved elephants. “[S]team on land, as well as on water, has been our best and most efficient agent of transportation in internal commerce,” he wrote in his 1862 letter to King Mongkut. Not letting it go at that, the keenly intelligent Lincoln also knew that the climate in the U.S. was unsuitable for elephants, who thrive in a tropical habitat. In an early example of “blaming the weather,” Lincoln told the king that the country “does not reach a latitude so low as to favor the multiplication of the elephant.”

Regrettably, many others with far fewer scruples had no such reservations. Just a few years after Lincoln put the kibosh on elephants as gifts, Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey Circus launched its mercenary business using elephants and other animals—a deadly tradition that would last nearly 150 years before the circus finally went dark in 2017. Many other circuses also took to exploiting animals and, like Ringling, most have rightfully been relegated to the history books.

Even 150 years ago, Lincoln recognized that animals are individuals with wants and needs entirely independent of humans. In acts both large and small, he made a difference. Shouldn’t we all strive to be a little more like Lincoln?