Recently, Smithfield Foods, the world’s largest purveyor of sausages, bacon, hot dogs and other artery-clogging pig flesh, announced a new venture: It wants to sell organs from the pigs it raises and kills for use in pig-to-human transplants.

In case the irony is lost on anyone, let’s break this down. A company that, for 80 years, has sold pig flesh to humans to eat—contributing to heart disease—now wants to sell pig hearts to replace human hearts that have given out after years of consuming unhealthy fare like Smithfield’s.

It’s beyond ironic; it seems almost devious—like if cigarette companies started marketing artificial lungs, or if booze producers got into the liver-replacement business. And if this plan ever comes to fruition, it will cause massive suffering—for animals who will be treated like warehouses for spare organs as well as for humans who will be exposed to the serious risks associated with receiving nonhuman transplants.

Pigs who are raised on Smithfield’s factory farms spend their short lives in cramped, filthy warehouses. These clever, loyal animals—who can play video games using joysticks and have been known to save their human families from fires and other dangers—are taken away from their mothers when they are as young as 10 days old. They are castrated, their tails are chopped off and the tips of their teeth are broken off with pliers—all without painkillers. Many are scalded alive in slaughterhouses.

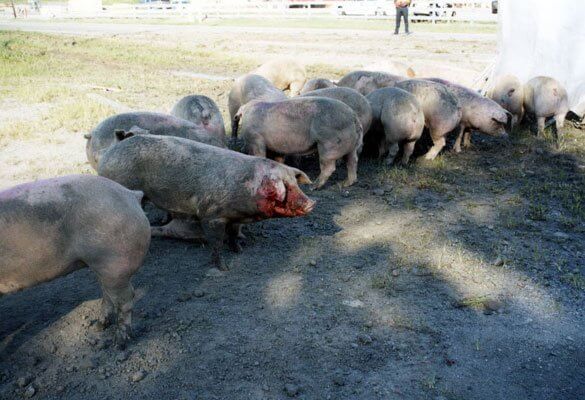

Cruelty is rampant in this industry, as it is whenever animals are treated as commodities. A PETA eyewitness investigation of one Smithfield supplier revealed that workers were hitting and jabbing pigs in the face with metal gate rods, dragging injured animals and depriving them of veterinary care.

Years of eating the flesh of these and other abused animals take their toll on people’s health. Cholesterol, which is found only in meat and other animal-derived foods, such as eggs and milk, is a major contributor to heart disease: Each additional 100 milligrams of cholesterol that someone consumes adds roughly five points to their cholesterol level. When too much cholesterol builds up inside a person’s coronary arteries, the heart loses some of its blood supply, putting the person at risk for a heart attack.

Granted, not everyone awaiting a heart transplant is in that situation because of what they eat. But whatever the reason, transplanting organs from one species into another is a reckless move. Xenotransplantation, as this practice is called, comes with the risk of infecting patients with dangerous animal-borne pathogens and potentially puts the public at risk for epidemic outbreaks. This is particularly worrying knowing the Smithfield “donor” animals would be housed on factory farms, which are cesspools of infectious agents, contaminants and superbugs. In addition, recipients of nonhuman organs would need to be administered higher levels of anti-rejection medication in order to facilitate the transplant, making them more vulnerable to other infections or even cancer.

Thankfully, we don’t need to resort to “Frankenscience” or entrust our hearts to companies that profit from peddling unhealthy products. We can get human organs to patients who desperately need them right now through a simple change in the law.

In Belgium, France, Sweden and other countries that have passed presumed consent laws—which presume that organs are available for donation upon one’s death unless an individual has opted out—or mandated choice laws—which require adults to choose between donating their organs or not—the number of organs available for donation has increased dramatically. Since changing its law in the 1970s, France, for example, has seen organ donations shoot up nearly 5,000 percent.

Breakthroughs in science and technology also hold hope for people awaiting transplants. Advances in sophisticated 3-D bioprinting now allow scientists to grow human tissue with precision and consistency. 3-D organs-on-chips are providing insight into diseases and offer the hope of personalized medicine by eventually allowing drugs and other therapies to be tested on a patient’s own cells.

The other living beings who share our planet aren’t organ factories, and trying to use them as such is cruel, misguided and dangerous. Pigs—and people whose lives depend on receiving healthy, human organs—deserve better.

By Dr. Emily Trunnell

Dr. Emily Trunnell is a research associate in People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals’ Laboratory Investigations Department