In Greek mythology, the sighting of a chimera—a creature composed of parts from more than one animal—was a bad omen.

I think it still is.

Experimenters at the Salk Institute made headlines recently with the publication of a study describing how they grew fetuses that were part pig and part human.

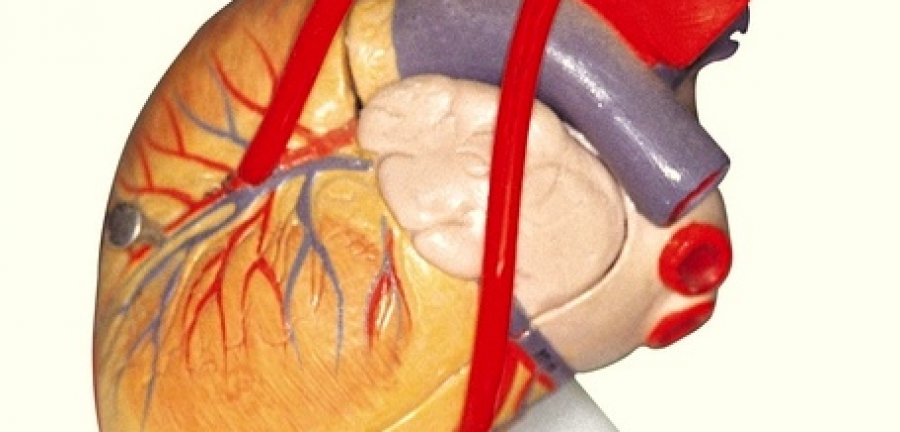

Although these chimeras contained few human cells, the work was widely hailed as a milestone—an initial step toward a far-off day when people in desperate need of transplants can order organs from warehouses in the form of living animals.

Leaving aside for a moment the unique ethical minefield that this line of research creates, let’s look at how patients in need of organs could be helped today, without subjecting intelligent, sensitive pigs to invasive procedures and then killing them—as was the fate of both the fetuses and the surrogate mothers who carried them in the Salk Institute’s experiments.

Just a simple change in law is all that is required. In Belgium, France, Sweden and other countries that have passed presumed consent laws, which presume that people’s organs are available for donation upon their death unless they opt out, or mandated choice laws, which require adults to choose whether or not to donate their organs, the number of organs available for donation has increased dramatically. For instance, since changing its law in the 1970s, France has seen organ donations shoot up by nearly 5,000 percent.

As for the rationale behind the Salk Institute’s study, its senior author is quoted as saying, “[O]rgans developed in petri dishes are not identical to the ones that grow inside a living thing. … What if we let nature do the work for us?”

“Petri dish” hardly does justice to the recent advances in sophisticated 3-D bioprinting that now allow scientists to grow human tissue in a highly controlled manner, with more precision and consistency than is possible in chimera experiments, in which tissue develops in live animals.

The same can be said of 3-D organs-on-chips, a technology that is not only providing insights into diseases—another justification given for chimera work—but also offering the potential for personalized medicine when, eventually, the efficacy of therapies will be able to be tested on a patient’s own cells. If we’re going to invest in long-term research to grow and study human organs, shouldn’t we pursue these pioneering, high-tech methods?

Because of the unique moral dilemma that chimera research presents, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) took the rare step in 2015 of imposing a moratorium on funding studies in which human stem cells are injected into animal embryos. (The Salk Institute experiments were privately funded.) While NIH has indicated that it intends to lift the funding ban in certain circumstances, I hope it will reconsider. Instead, it should support forward-looking, non-animal methods of developing replacement organs and researching disease.

We need to leave behind the ancient world of mythological creatures and embrace the promising, cutting-edge technologies that will alleviate the suffering of both animals and humans.

Dr. Emily Trunnell is a research associate in PETA’s Laboratory Investigations Department