An octopus named Inky showed the world just how clever these animals are—and how much they long to be free—when he made his now-famous escape from the National Aquarium of New Zealand. When the lid of his tank was left slightly ajar one night, he apparently climbed out, slid down the side, and scrambled across the aquarium floor to a 146-foot-long drainpipe that led to the sea—and freedom.

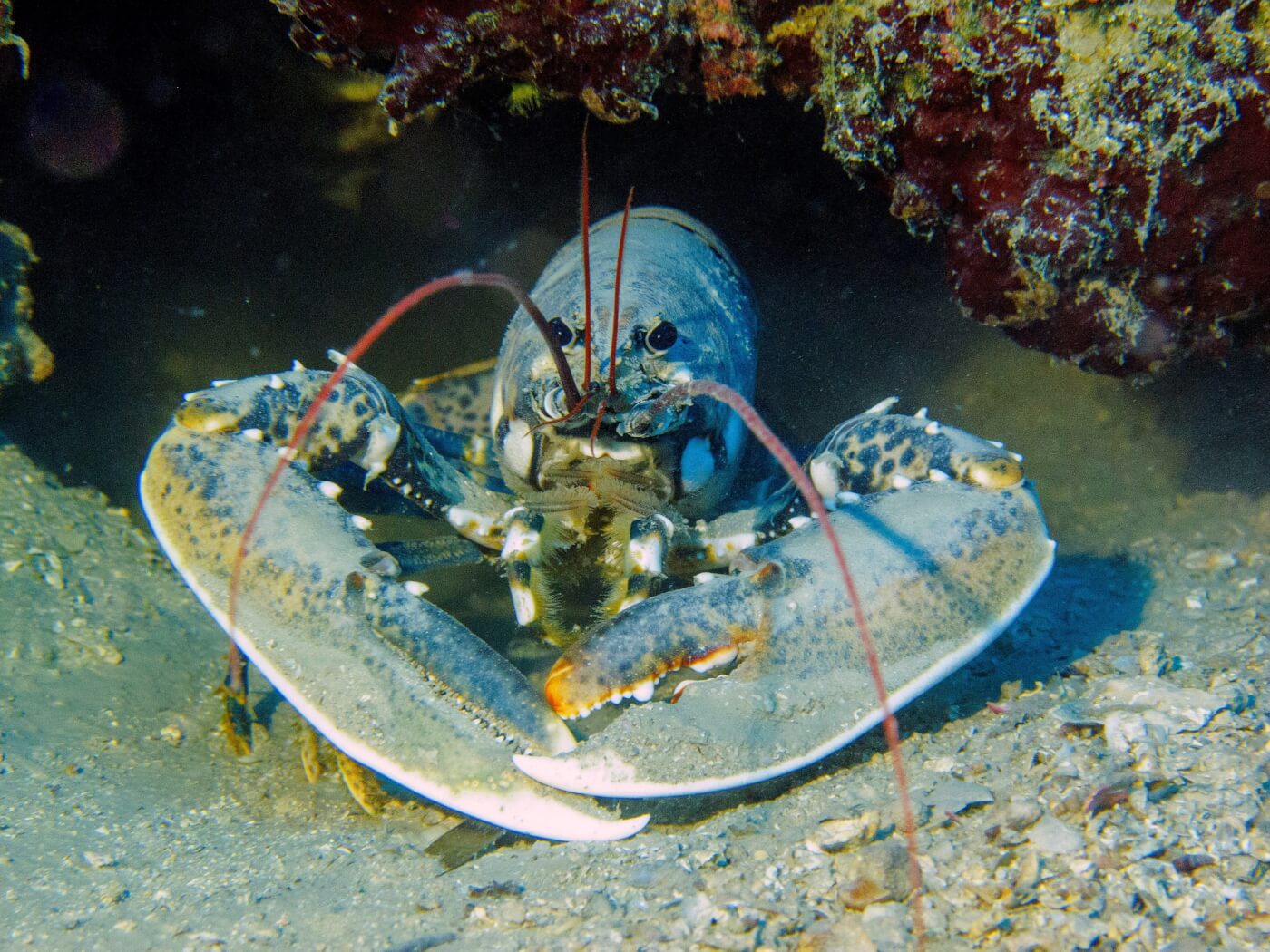

Octopuses are so smart that they’re sometimes called “primates of the sea” and compared to intelligent aliens. Yet they, lobsters, and other aquatic animals are often treated as if they had no feelings at all and as if their lives counted for nothing.

One particularly disturbing PETA exposé revealed that some restaurants hack apart octopuses and serve them to diners, still alive and writhing in pain. And PETA’s exposés of lobster suppliers and slaughterhouses revealed that workers dismember conscious lobsters and crabs by tearing off their claws, puncturing their shells, ripping their heads off, and impaling them on spikes. The common “cooking” method for lobsters involves dropping them, while still alive, into a pot of boiling water. They thrash about frantically and claw at the sides of the pot in a desperate attempt to escape.

Even most meat-eaters would be appalled if a live, dismembered pig were brought to their table or if a chicken were boiled alive in front of them.

So what causes the ethical disconnect that makes some people think it’s OK to abuse aquatic animals in these ways? Perhaps it’s because shellfish live underwater and look so different from land animals. But while shellfish may not make facial expressions that we recognize or scream when they’re cut apart, their reactions fulfill the scientific criteria for pain. They have complex nervous systems, try to escape from harmful stimuli, show physiological stress responses, and guard their wounds. They feel pain every bit as keenly as other animals do.

According to Dr. Jennifer Mather, an expert on cephalopods and a psychology professor at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, Canada, “[T]he octopus, which you’ve been chopping to pieces, is feeling pain every time you do it. It’s just as painful as if it were a hog, a fish, or a rabbit, if you chopped a rabbit’s leg off piece by piece. So it’s a barbaric thing to do to the animal.”

Lobsters may feel even more pain than humans or other animals would while being boiled or cut apart. That’s because, according to invertebrate zoologist Jaren G. Horsley, “The lobster does not have an autonomic nervous system that puts it into a state of shock when it is harmed. It probably feels itself being cut. … I think the lobster is in a great deal of pain from being cut open … [and] feels all the pain until its nervous system is destroyed” during cooking.

Recognizing this, Switzerland made it illegal to boil these animals alive, and the practice is also banned in New Zealand and Reggio Emilia, a city in northern Italy. Perhaps if people knew more about these fascinating beings, they would be moved to show them compassion and leave them off their plates.

Many shellfish have impressive abilities. Lobsters, for example, “smell” chemicals in the water with their antennae, and they “taste” with sensory hairs along their legs. They use complicated signals to explore their surroundings and establish social relationships. They take long-distance seasonal journeys and can cover 100 miles or more each year.

Hermit crabs who outgrow their shells have been observed lining up by size so that multiple individuals can switch shells and “upgrade” at once. Dresser crabs create custom camouflage for themselves by sticking sponges and seaweed to the Velcro-like hooks on their legs and shells.

Some shrimp live in complex colonies similar to beehives, while others mate for life. Cleaner shrimp provide fish with a mutually beneficial service, communicating with potential “clients” by waving their antennae and sensing fish’s changing colors.

Crayfish have keen memories, remembering (and avoiding) opponents who’ve beaten them in past fights. They also experience anxiety and respond to the same drug that has been used to treat the condition in humans.

Scallops can escape predators by flapping their shells, and clams take refuge by burying themselves in the sand. Oysters snap their shells shut at a threat and change their sex at least once during their lifetimes.

Octopuses can mimic other aquatic animals, unscrew jars to get a meal, distinguish between shapes, quickly find their way out of mazes, disguise themselves as rocks to evade predators, play with toys, and more.

Shellfish have many unique qualities, but they share several important ones with all animals: They feel pain and fear and long to be free. They should have a right to live in peace. It’s so easy for us to spare them immense pain and suffering simply by not eating them. Ready to extend your compassion to all living beings? Pledge to go vegan!