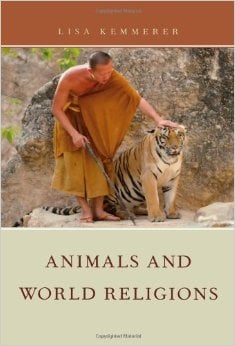

Kemmerer’s exhaustively researched text examines the core moral teachings of seven of the world’s major religions—Buddhism, Chinese traditions (Confucian and Daoist), Christianity, Hinduism, indigenous traditions, Islam, and Judaism—with regard to animals and our treatment of them, including eating them, hunting them, keeping them in captivity, and using them for sport. As Gandhi said, “The soul of religions is one, but encased in a multitude of forms,” and indeed, by thoroughly examining both sacred texts and the lives of moral exemplars, Kemmerer makes a persuasive case that all of the world’s great religions not only teach love and compassion for animals but require those who are sincere in their faith to act with compassion in their dealings with animals. To Kemmerer, acting with compassion toward animals means, at the very least, not eating them.

“If there were no meat-eaters, there would be no killers. A meat-eating man is a killer indeed,” we read in the sacred Hindu epic the Mahabharata. The Buddhist text the Dhammapada teaches, “All beings fear before danger, life is dear to all. When a man considers this, he does not kill or cause to kill.” Mencius, the most famous Confucian sage after Confucius himself, wrote, “So is the superior man affected towards animals, that, having seen them alive, he cannot bear to see them die; having heard their dying cries, he cannot bear to eat their flesh.” The Jewish Tanakh (what Christians call the Old Testament) reminds us that “[m]an has no superiority over beast” (Ecclesiastes 3:19).

Kemmerer then brings the foundational teachings of each religion into the real world with profiles of historic and contemporary figures who have put their faith into action by speaking out for animals, going vegan, and in some cases, raiding factory farms and laboratories. These inspiring animal advocates include former PETA India staffer Anuradha Sawhney, Zen master Thich Nhat Hanh (who gave PETA his blessing to use one of his pro-vegan statements in a beautiful ad), Judaism and Vegetarianism author Richard Schwartz, and many others.

While Animals and World Religions is not always an easy read, this thought-provoking book should be required reading for people who say that they are religious but seem to think that they need not take animals into consideration. (If you know someone like that—don’t we all?—you might ask them to read, at the very least, the chapter that discusses their particular religious tradition.) Not all of the religions discussed here explicitly require the faithful to be vegetarian, but Kemmerer makes clear that none of them would condone the egregious abuses that are common practice on today’s factory farms (which are outlined in a concise and compelling appendix), and therefore, the faithful have no choice but to stop eating animals. In other words, if you say you believe in love and compassion, practice what you preach. As Kemmerer writes in the conclusion, “Indigenous peoples, Hindus, Buddhists, Daoists, Confucians, Jews, Christians, and Muslims are obligated to either change basic habits of consumption or admit that they don’t care about the most fundamental teachings of their religion—that they aren’t religious after all.”

Has your faith informed how you view and relate to other animals? Tell us in the comments.